“There was a point a year and a half ago when I wondered whether I would be doing this again,”…

Author: Uncut

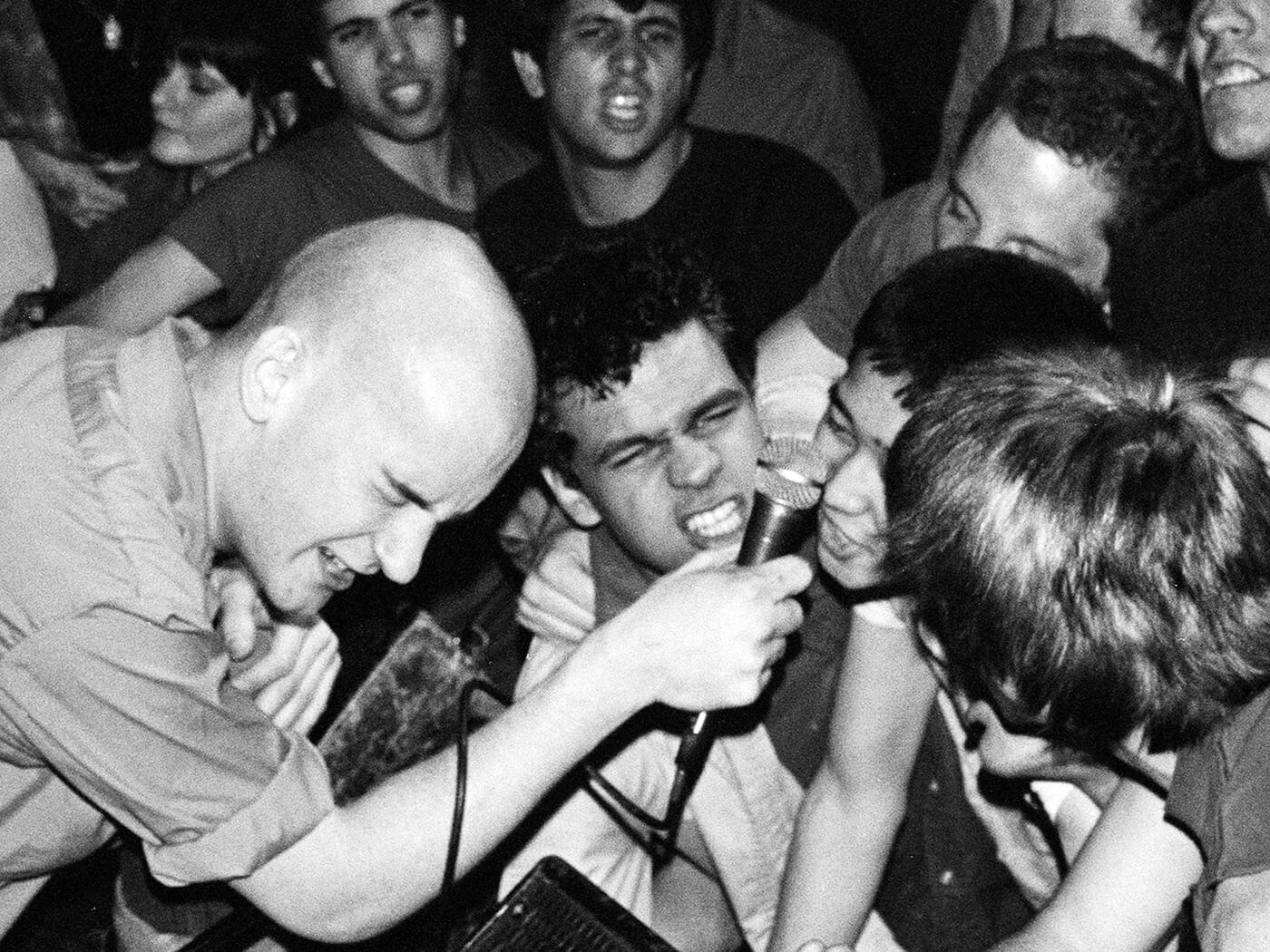

D.C. Punk Scene Documentary: ‘Punk the Capital’

By Jim Wirth As they bickered throughout the final days of Minor Threat, drummer Jeff Nelson told singer Ian MacKaye…

Kings Of Convenience – Peace or Love

On the cover of Peace Or Love, the long-awaited fourth album by Eirik Glambek Bøe and Erlend Øye, the Norwegian…

BLK JKS drop first album in 12 years, ‘Abantu/Before Humans’

Bands like BLK JKS don’t come along often, especially in places like Johannesburg. There was no South African indie rock…

David John Morris – Monastic Love Songs

Take a map and find Gampo Abbey, a Buddhist monastery situated on a rugged finger of Nova Scotia, Canada, and…